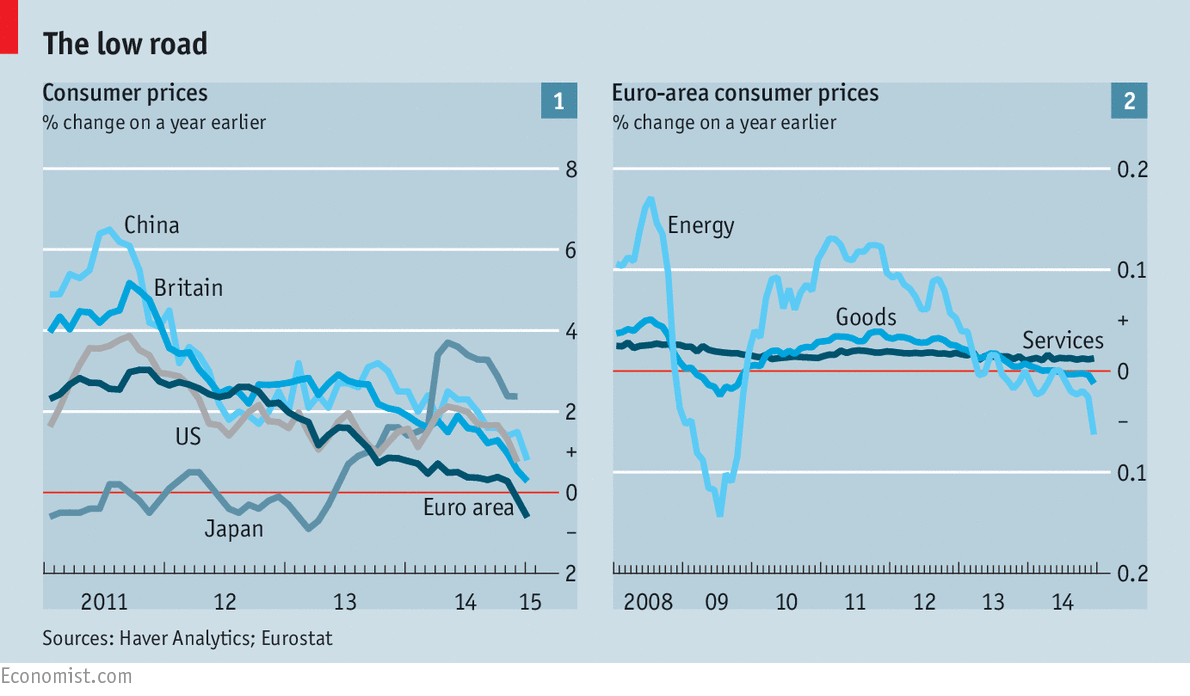

The reason why it is a problem is because aggregate prices are dipping in so many places at once. Deflation is affecting a wide range of goods other than food and energy as well as countries that cannot claim to be leading the charge towards the new economy. This appears to be a sign of entrenched weak demand. Besides that, consumers will put off spending hoping that prices will fall even more in the future, further decreasing demand. Also, if prices fall but wages do not, it will increase the cost of production for firms and may lead to a decline or a stagnation in employment. Another risk is debt deflation. This means the value of debt will rise because the amount that is owed remains the same even if earnings fall. This is an especially big issue in the euro zone where many banks are already stuffed with dud loans.

The most severe danger is the fact that it is already here. Deflation makes it more difficult to loosen monetary policy. When inflation is at 4%, the central bank can take real interest rates below zero, to -4% by retaining headline rates at zero. But as inflation falls and turns negative, low real interest rates get harder and harder to achieve- just when you need them most. Most rich-world central banks have reduced their main policy rates close to zero to increase demand. The use of negative interest rates in a growing number of European economies to encourage spending will backfire as charging consumers to save in banks will eventually prompt them to use the mattress instead.

The most severe danger is the fact that it is already here. Deflation makes it more difficult to loosen monetary policy. When inflation is at 4%, the central bank can take real interest rates below zero, to -4% by retaining headline rates at zero. But as inflation falls and turns negative, low real interest rates get harder and harder to achieve- just when you need them most. Most rich-world central banks have reduced their main policy rates close to zero to increase demand. The use of negative interest rates in a growing number of European economies to encourage spending will backfire as charging consumers to save in banks will eventually prompt them to use the mattress instead.This means that policymakers have little room for manoeuvre when the next recession hits, which will happen in due course. It may be caused by China's slowdown in growth, or from the effect of a rising greenback on dollar-denominated corporate debt, or possibly from a random shock. In America, the Federal Reserve reduced interest rates by 3.9 percentage points on average in the six recessions since 1971. That move would not be possible today. The emergency measure of depreciating the currency drastically against a fast-growing trading partner would also not work because not many economies are growing rapidly and prices are falling, or close to it, in so many places.

Policymakers should take this problem more seriously and take bolder action to avoid deflation. Governments ought to increase spending on infrastructure to boost demand. The central banks should err on the side of looseness. Perhaps it is time to change the central banker's target for interest rates from the inflation rate to a goal for the level of nominal GDP. With this kind of target there would be no need to differentiate between good and bad price shocks. This would also send the message that policymakers are serious about getting rid of deflation.

On the other hand, central bankers change course slowly and they are exceptionally loyal to their inflation targets. Their conservative nature often serves them well. However in this case, it could cost the world economy dearly.